The Eternal Alphabet Dispute in Central Asia

Since the collapse of the USSR, the five former Soviet republics of Central Asia have been debating whether to abandon the Cyrillic alphabet in favour of Latin script. Some argue it more closely reflects the phonetics of Turkic languages, but the issue is entangled with broader calls for “de-Russification” in the context of the war in Ukraine. Even in Kazakhstan—where Nazarbayev launched the transition with the aim of completing it by 2031—serious doubts remain.

Astana (AsiaNews) – Since the end of the Soviet Union and the emergence of independence in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, debate has persisted in these five Central Asian countries—as well as in Azerbaijan in the Caucasus—over the need to abandon the Russian Cyrillic alphabet, imposed by centuries of occupation, and instead adopt Latin script. Latin is considered more universal and better suited to the phonetics of the various Turkic languages spoken across the region, although these languages differ significantly from each other and also from modern Turkish.

The only country to have sidestepped the debate entirely is Kyrgyzstan, where Russian remains a second official language, and both alphabets continue to be used side by side. In recent years, however, the issue has regained urgency, seen as a form of “de-Russification” amid the backdrop of the war in Ukraine and potential Russian threats to these territories—especially northern Kazakhstan—which Moscow views as part of the broader “Russian world.” Currently, Latin script is used officially only in Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.

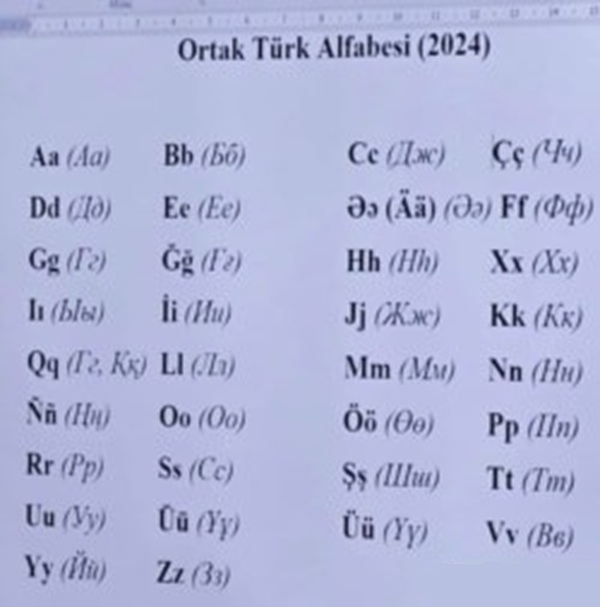

Last September, Baku—the capital of Azerbaijan—hosted a conference of the Organisation of Turkic States focused on linguistic matters. Experts converged around a shared Turkic Latin-based alphabet. A new scientific conference on the topic is expected soon in Baku, especially significant given that the first “Turkological” congress took place in the Azerbaijani capital a century ago, in 1926. That event led to the abandonment of the ornate and archaic Arabic script in favour of Latin letters. A decade later, however, the Soviet authorities replaced Latin with Cyrillic by decree.

Uzbekistan began its transition to Latin script in 1993, with plans to complete the process within seven years. But the reform never fully materialised. In January 2023, a government decree ordered the mandatory use of Latin script for all official documents and media publications. Alisher Ilkhamov, an independent Uzbek scholar now based in the UK, published an article titled The Forced Transition of the Uzbek Language to Latin Script: Consequences for Uzbekistan’s Population. In it, he warned that the decision could cause deep societal rifts: older generations would retain access to knowledge in Cyrillic, while younger people could be cut off from much of the country's literary heritage.

Ilkhamov describes the Latin script as an “instrument of ideological pressure,” arguing that it is merely a “system of symbols” and that the idea it better represents Turkic phonetics is an illusion. Ultimately, he says, meaning lies in shared conventions about the correspondence between signs and sounds—regardless of the alphabet used. Kazakh Turkologist Erden Kazhybek takes a more nuanced view, noting that the success of such linguistic reforms “always depends on socio-political conditions” and that people must be given time to adapt to change.

In Kazakhstan, the transition to Latin script began in 2017 under the country’s “eternal president” Nursultan Nazarbayev, and was initially scheduled for completion by this year. However, resistance has been even stronger than in neighbouring countries—partly due to the sizeable Russian-speaking minority. Kazhybek points out that “all the proposed variants were top-down decisions, with significant differences between them,” and admits, in his role as chair of the official committee, “I had no idea what decisions to make.” The committee was later dissolved, and scholars have since attempted to weed out less suitable variants and promote a more widely accepted approach to script reform. Current President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has acknowledged that “many silly mistakes” were made, and that it is now necessary “to reach a more sensible decision together.” Kazakhstan’s new alphabet is due to be finalised by 2031, and across Central Asia, people await a form of written expression that truly reflects a cultural space suspended between continents.

.png)