Indian plastic chokes Ram Setu, 'Adam's Bridge'

A new environmental emergency has hit the strait separating the Indian coast from Sri Lanka, threatening to cripple local tourism and fishing. Carried by currents from India, mounds of plastic reach the Mannar region. Monsoon currents, which carry dust, are more difficult to collect, compounding the problem. Globally, the failure to ratify or implement agreements and treaties weighs heavily on the country.

Colombo (AsiaNews) – Sri Lanka is facing a major environmental emergency that threatens to deal a severe blow to tourism and fishing, two of the main industries in the South Asian nation's economy.

Currently, the coastlines of Mannar (Northern Province) are buried under large mounds of plastic brought in by waves coming not only from within the country, but also and especially from neighbouring India in what constitutes “transboundary pollution”.

According to many environmentalists, this year's situation is even worse than in the recent past with the southern coast leading to Adam's Bridge covered in plastic waste.

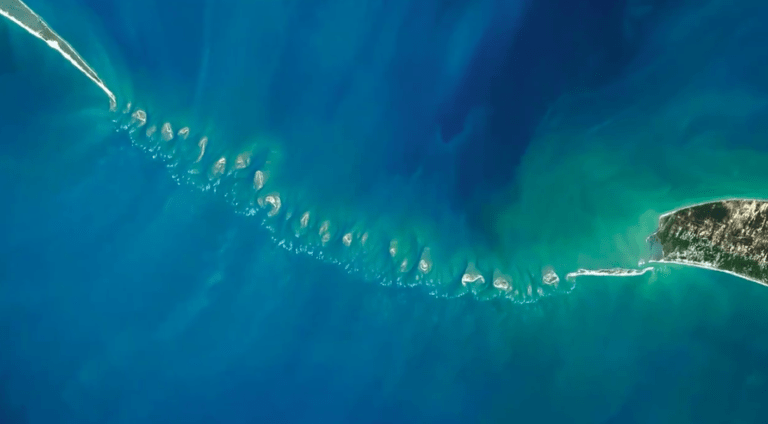

Also known as Ram Setu, the 48-kilometre-long limestone shoals connect Pamban Island (also known as Rameswaram Island), the largest of the Tamil Nadu group located between peninsular India and Sri Lanka, to Mannar.

Although the Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA) performs regular cleanup to remove plastic pellets (nurdles), the plastic dust dispersed by monsoon winds is harder to collect. For local communities, the problem is getting worse with each season.

“Although some plastic debris washes away during the rainy season, monsoon currents typically push the debris toward Sri Lanka,” said Kithsiri Ramanayaka and Anuradha Paranawithana, two environmentalists who spoke to AsiaNews.

“Since most countries fail to address their domestic waste management problems, plastic will continue to circulate through ocean currents,” they added. “Plastic pollution in Mannar has disastrous ecological consequences," especially for marine wildlife that “ends up ingesting or becoming entangled.”

Habitat degradation and the disruption of production cycles causes “"a decline in potential fish populations and health risks for local fishermen who depend on marine resources for their livelihoods."

The experts warn that, "Addressing this problem requires a cross-sectoral approach involving collaboration between various sectors, including the fishing industry, waste management sectors, and local authorities.”

To this end, “Adequate sampling is needed to determine the impact of 'plastic dust’, which has not been done so far. According to available data, Sri Lanka's coasts receive plastic from South and Southeast Asia.”

Scholar Ravihari Alwis and Nishantha Gamlath share these concerns, and for them, “the issue must be addressed immediately.”

In 2022, the 193 United Nations member states agreed to develop a legally binding international treaty to end plastic pollution, addressing its entire life cycle from production to use and waste disposal.

Despite five rounds of negotiations, the last in April in Kenya, no agreement has been reached, while the follow-up session in Geneva also failed. At the same time, the sixth round of negotiations of the Global Plastics Treaty (legally binding to address the problem of plastic waste) also failed. However, a treaty is still considered crucial, as it would place greater responsibility on the richest plastic-producing nations.

For the experts, there are two key issues, namely whether the entire life cycle of plastics, starting with production, and their health implications, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals, should be included in the treaty. Oil-producing countries oppose these measures.

Overall, “island states such as Sri Lanka, compared to producers and users, face the brunt of plastic pollution”, and call “for the full cycle to be included.”

Arjun Pathmarajah (46) and Neelan Ravichandrarajah (39), social and environmental activists in Mannar, are aware of the major issues.

“Apart from plastic pollution, there’s plastic dust in the air, too, brought by the winds. We usually get a lot of it, but this time it is intense. We speculate that the trash is coming in from India. The pollution has an extremely bad impact on the environment and our ecosystems, including on groundwater, fish, the primary source of income of the community and health consequences.”

The Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA) has been coordinating cleanup operations in co-operation with the military, government authorities, including the Central Environment Authority, local NGOs, and communities in several coastal regions. Several teams have been deployed to Mannar to address the debris that washes ashore.

24/01/2007

.png)