‘Nuclear weapons and humanity cannot coexist’: Hiroshima's cry about the 'forgotten danger’

One of the survivors of 6 August 1945 spoke at the Community of Sant'Egidio peace summit in Rome, saying that she continues “to believe in human wisdom”. She was joined by the bishop of the Japanese martyr city, Alexis Mitsuru Shirahama, who said: "We have little time left.” For Susi Snyder, “Deterrence is not demonstrable.”

Rome (AsiaNews) – It all happened "in an instant”; the time it took for a "blinding flash" to appear, preceded by a shout: "Enemy plane!" Tanaka Katsuko was six years old in Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. "My eyes went white and I couldn't see anything," she said. I had “a bitter, grainy taste in my mouth."

At 87, she is one of the last surviving hibakusha, atomic bombing survivors. She spoke this morning at the Community of Sant'Egidio's international peace summit, held in the auditorium of the Museo MAXXI in Rome.

As a speaker at the forum The Forgotten Danger: For a World Without Nuclear Weapons, she remembers seeing clearly again, through a crack. “The memory of that blue sky sustained me through every difficulty," she said.

After the war, she became an artist, creating "enamel murals”, with which she sought to “evoke the trauma." Then came a commitment that turned into a mission: "To share the message that nuclear weapons and humanity cannot coexist.”

One of Tanaka Katsuko's children, a daughter, heeded that message; in Rome she explained that she too felt a “responsibility” to pass it on to the world.

Such a message is not merely a rumination about the past, but something that is still relevant today, across generations, just like the devastating effects of radioactive radiation had on human health.

This is especially true now, when more than 12,000 nuclear warheads are seen as a “deterrent” in the name of phoney security.

The mother and daughter stories are “a bridge between the people who are no longer with us and those who remain," said Andrea Bartoli, president of the Sant'Egidio Foundation for Peace and Dialogue, who moderated the meeting.

Bartoli added that one of humanity's challenges today is “to transform the threat into an opportunity," an action possible by converting arsenals into huge quantities of energy.

He compared the "blue" Tanaka Katsuko saw when she regained her sight to the symbolic colour of the United Nations, established in the aftermath of the Second World War, from the "precious effort to build something different on the memory of that suffering."

The commitment to disarmament and global peace concerns every person. “Peace begins in the heart of each of us," Tanaka Katsuko said. “We are all crew members aboard the ship Earth." Despite the immeasurable trauma, she continues "to believe in human wisdom”.

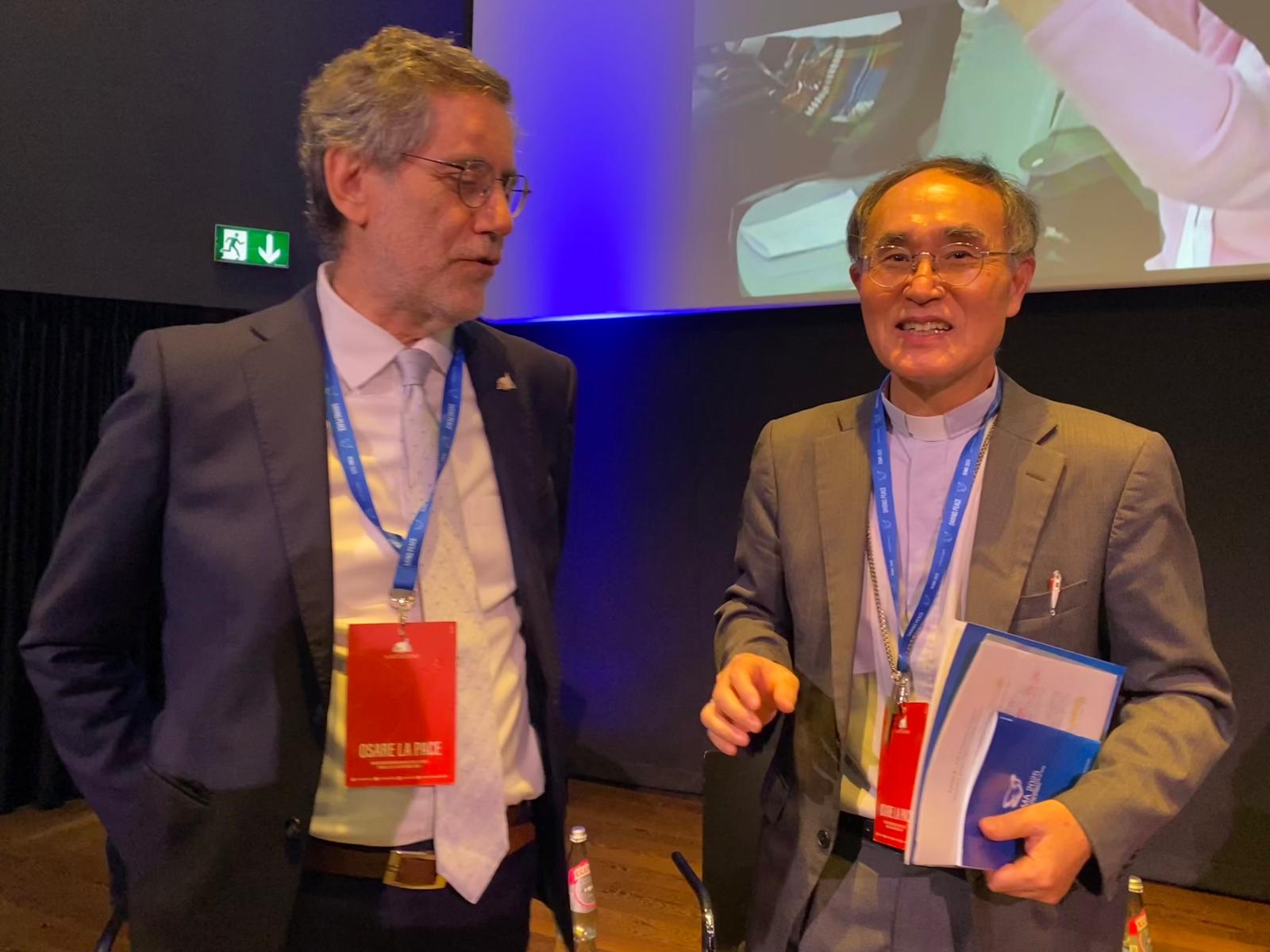

Bishop Alexis Mitsuru Shirahama of Hiroshima also spoke at the forum dedicated to the "forgotten danger" of nuclear weapons. In his address (in Japanese), he mentioned the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“We are moving to a generation that does not know the horrors of war and the atomic bomb," he warned. Citing Pope Francis's visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in 2019, he cites the late pontiff’s words, and called the use of nuclear weapons "immoral”, and emphasised the importance of remembering, journeying together, protecting.

For the Japanese prelate, the current situation, despite legally binding international treaties, appears "out of control”. If the threat were to materialise today, the impact would be “incalculable”.

Bishop Shirahama cites in particular the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which came into force in 1970, signed by 191 states, as well as the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) of 2021, signed by more than 90 states.

However, the countries with nuclear arsenals "are turning their back" on these agreements, he lamented. "We cannot abandon our efforts," he insisted. He cites a hibakusha who urged him not to worry about the past, but "about the period of humanity's extinction due to nuclear weapons."

For the bishop of Hiroshima, religious leaders have a responsibility as "promoters of peace" and "bridges”. But he fears “We have little time left.” This is why today, more than ever, "small steps" are needed, like those taken by the Churches in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, setting up a fund for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

“We have a partnership with the archdioceses of Seattle and of Santa Fe (US), which suffered the effects of the Los Alamos nuclear tests," Bishop Shirahama told AsiaNews at the end of the meeting. "We are also raising funds to engage and support the surviving hibakusha. This is a five-year project with which we also want to support the TPNW.”

For Japanese clergymen, the dwindling number of survivors is a worrying fact. "By getting them involved, we must begin to think about concrete actions to engage and raise awareness among the new generations," he told AsiaNews.

“Material progress is not accompanied by spiritual evolution. We must rediscover human spirituality so that humanity is not completely destroyed,” he added.

Another speaker at today's forum was Susi Snyder of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017.

According to Snyder, deterrence “is not demonstrable” and “the possibility that it could fail is real.” There is a risk, she stressed, of "normalising" the nuclear threat.

She also underscored the importance of a legal framework for achieving its elimination. Otherwise, “Once the button is pressed, there is no going back," she said.

Finally, sociologist Fabrizio Battistelli, in his address about the "nuclear taboo”, spoke about the surprise Nobel Peace Prize awarded in 2024 to the Japanese organisation Nihon Hidankyo, which represents atomic bomb survivors. He sees this as an invitation to revisit the nuclear threat, which still pervades public discourse today, as evinced by the wars in Ukraine and Palestine.

06/08/2020 10:04

06/08/2019 13:55

.png)