Literature greatest weapon against dictatorship in Russia

Books and essays are among the tools traditionally used to oppose regimes. Sales of books on the “difficult pages” of the past are on the rise. Research into stories about dictatorships and the lives of ordinary people under them is very popular. Sales of stories about the crimes of autocrats have grown by 70%. However, historians and writers of utopian novels are now banned.

Moscow (AsiaNews) - In Russia, literature has traditionally been one of the main tools of opposition to dictatorships, from the Tsarist to the Soviet regimes, and now also in Putin's Russia, which, not surprisingly, is tightening its grip on censorship of all types of “unpatriotic” publications, both in print and digital formats.

Since the spring of 2022, Russians have been rereading stories about the crimes of Nazi Germany, life during the Third Reich and how the country rebuilt itself after the devastation of the Second World War, a scenario very similar to what is happening in Russia today.

Even this historical literature, which is apparently fully in line with the rhetoric of victory over today's Western “Nazis”, has become a form of criticism of the Kremlin's authoritarian and aggressive regime, and its dissemination is also viewed with suspicion, with only official versions approved by state bodies being allowed to be read.

One of the most sought-after texts since the mobilisation in the autumn of 2022 has been “The Mobilised Nation” by Nicholas Stargardt, an Australian historian at the University of Oxford, who studied the private correspondence of Germans at the time of Nazi mobilisation, seeking to understand how the war could be justified and how many reacted by considering the war an injustice, an act of ferocity and genocide. In fact, this book was soon banned in all bookshops and libraries in Russia.

As critic Boris Grozovskij observes on his Telegram channel, one of the foundations for understanding events is precisely the analogy at the historical level, which allows us to overcome the lack of information.

This approach is favoured by literature, which, in a context of indecision, confusion and growing censorship, allows us to compare different situations without going into the details of current events, taking on meanings beyond the official or apparent ones, without running too much risk of repression.

The mechanism of analogy, after all, is the basis of any interest and curiosity about history, seeking to understand the present through the past.

Since no two situations are identical and perfectly coincidental, the work of professional historians consists of “identifying all the open questions, opening the reader's mind to new considerations”, as political scientist Ivan Krastev writes in Foreign Policy.

Historical analogies can be “risky or random”, but they highlight “not only similarities but also differences, becoming very useful tools for analysis” and for imagining the political and social prospects of the future.

According to research by Natalia Vasilenok of Stanford University, Russia's leading book networks today, such as Čitaj-Gorod and LiveLib, show continued growth in sales of books on the ‘difficult pages’ of the past, which are impossible to censor in their entirety.

People are looking for stories about the many dictatorial regimes, about the lives of ordinary people under them, and the crimes of autocrats are one of the most read topics, accounting for 70% of sales. Restrictions on this literary sector have also begun in recent months, with assessments that ‘discussing wars can discredit the Russian armed forces’.

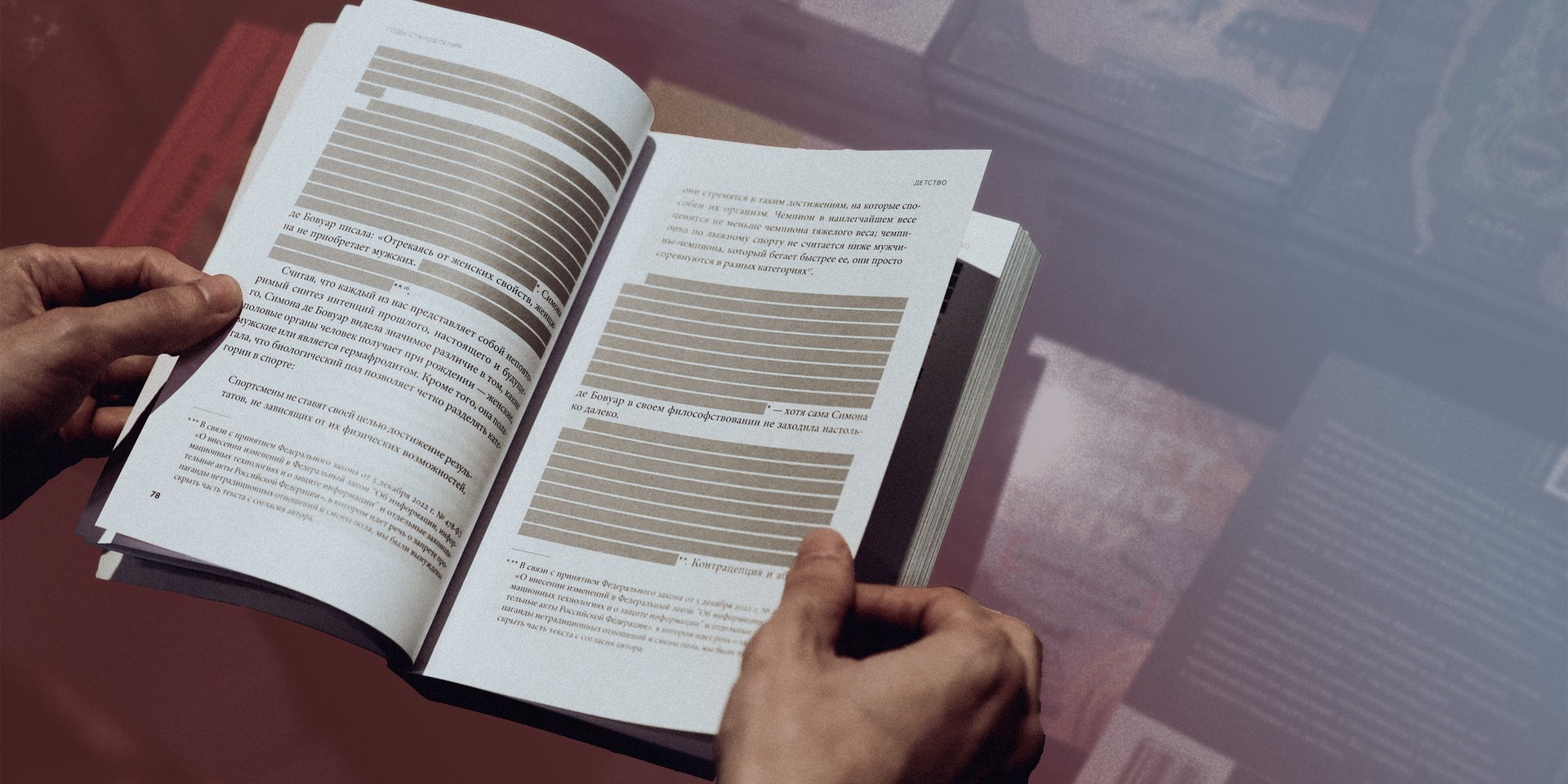

Historians and writers of utopian novels are now banned, such as Vladimir Sorokin, Russia's leading author today, but also foreign authors such as Michael Cunningham and James Baldwin, who are easily accused of “LGBT propaganda” for their stories about “non-traditional” aspects of life in today's and yesterday's societies.

Since April this year, the Russian Writers' Union has begun operating a very Soviet-style “expert centre” for historical re-enactment, to verify the “compliance of each book with Russian legislation”, with the official revival of censorship of words and thoughts.

The symbol of this new/old phase of enforced silence was the ban on the publication of Konstantin Pakhalyuk's book, “In Search of Russian Antiquity”, to prevent a look into the past from revealing the reality of today's Russia.

07/02/2019 17:28

11/08/2017 20:05

.png)