The Porgera Valley, land of gold and despair

It was supposed to be a land of promises for those who had always lived from subsistence farming. Thanks to the employment brought by the mine, they had access to modern education and healthcare. But the end of the licence and a vicious cycle of tribal struggles have sown death and desolation. The government of Papua New Guinea has recently negotiated the mine’s reopening. But with many unknowns about the future.

Enga (AsiaNews) – The suburb of Paiam is at the entrance of the Porgera Valley, 2,500 metres above sea level, in the remote Enga Province of Papua New Guinea. It was developed in the late 1990s to accommodate the increasing number of national personnel working at the gold mine which opened in 1990. It was provided with a police station, post office, bank, and an international school. The Catholic Church rushed to open the new parish of Blessed Peter to Rot in 2002. Now, the few people remaining there, point at the four residential villages totally abandoned, the almost empty church, and the modern hospital hopefully soon to reopen, but still closed. The people have gone. The mine ceased operations between 2020 and early 2024. During the same years, the locals around Paiam entered a vicious cycle of tribal fight that scared everybody away. Not only were the mining villages ransacked, but the houses and commercial establishments of the members of the local clans were burnt down.

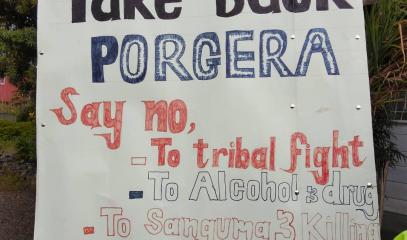

Now it looks like, with the reopening of the Porgera mine under a new agreement between the Government and the mining companies, the desire for a tribal peace is also there with a gradual return of the residents. But it will take years before Paiam is again the same lively place that we could still see in 2019. The tribal fight that caused such devastation, a common occurrence in Enga, was simply about the financial benefits and shares of a compensation for a communication tower between real and purported landowners in the area. As soon as the first killings took place, the cycle of retaliation became unstoppable. With indescribable sadness in their eyes, a group of youths after the Mass on Holy Thursday told me of the gruesome assassination of their Church leader a few years back.

The Porgera Valley was supposed to be a land of promise. The first alluvial gold was spotted in 1938. Christianity settled in this remote area of Papua New Guinea only after the latter half of the last century. The first Catholic parish was established at the Mungulep village in 1966 by the Missionaries of the Society of the Divine Word (SVD). The gold and silver mine opened in 1990 with a thirty-year licence from the Government. The project had reasonable benefits for PNG stakeholders (the National Government, the people of the area, the Enga Province, and the country as a whole). In the span of one generation, a few thousand people, who had always lived by subsistence farming, found themselves exposed to modern education and health, the cash economy and the receipt of mining royalties. Ancestral lands and gardens gave way to an open pit mine, mineral processing plants, roads and fuel depots, paid employment; and young people learnt totally new things from the traditional agricultural techniques. Stores rather than gardens started providing food. It went on that way till the temporary closure of the mine at the expiry of the term of the mining licence in 2020 and the simultaneous eruption of the tribal fighting at Paiam.

That year the Marape-Rosso National Government, under the political slogan Take Back PNG, decided to substantially renegotiate the mining agreement. The objective of the Government was to secure a 51% equity share for PNG stakeholders, basically the National Government (36%), the Provincial Government (5%), and the landowners (10%). This was expected to provide more than US$ billion overall income over the estimated remaining 20-year life span of the mine, about PGK 30 billion depending on the fluctuation of the local currency. In turn, some 49% of the so-called New Porgera Limited is owned by Barrick Niugini Limited, itself a joint venture between Barrick Gold of Canada and Zijin Mining of China. Barrick has operated the mine since acquiring it from Placer Dome almost twenty years ago in 2006. Porgera is rated one of the ten top gold mines in the world, providing 10% of Papua New Guinea’s national exports, and it employs about 3,000 national employees.

During the initial years of Barrick management, the Canadian media and other international outlets reported deterioration in the company’s relationship with the local population. In 2010, Barrick paid compensation to 119 survivors of sexual assault by their security guards against residents ("MINING #7 - Barrick and the Cruelty of Gold"). The current reopening of the mine has been accompanied by a considerable level of violence, which though not on account of Barrick, has prompted intervention by the police with army reinforcements by the Government. The three-year closure had deprived the local people of job opportunities and family income, throwing thousands into poverty after decades of relatively well-off conditions. An increase in alluvial mining and illegal practices has arisen as one of the consequences of the closure, including illicit entry into the restricted Special Mining Lease area.

Mine workers confirm that illegal trespass into the mining area is still happening. Often, and at considerable risk in connection with the mine dynamite blasts, young people rush into the pit area before security guards are able to intervene with tear gas and prevent them from grabbing any amount of the ore. In the process, deaths have been recently reported. Incidents also occur among alluvial miners competing with and stealing from each other before reaching the gold buyers in town, or between local landowners and outsiders settling in the mine area in the hope of securing part of the profits. According to locals, lives are lost almost daily. Alluvial mining is not a small business, and outside the Special Mining Lease area, it is legal and widely practised. The fundamental error of the government and the company was to not properly resettle the residents, as per standard practice, away from the prospective mining site, thus mitigating the health and security hazards.

The new agreement for the reopening of the mine in December 2023 bodes well for the landowners should the level of violence and lawlessness be steadily contained and possibly be eliminated. The population of the community has significantly increased over the years since mine opening, so the individual share of the available financial benefits under the new agreement is reduced, but they are still significant given certain conditions. The first is obviously that they properly manage their benefits with collective or individual accounts of the landowners, despite the chronic risks of corruption and mismanagement. The second is that the benefits are properly used, such a being spent with a priority on schooling for the new generations.

Education has taken a significant toll with the closure of the mine and the displacements caused by the tribal fighting in Paiam. Gone are the years of the great efforts by the Governor of Enga, Peter Ipatas to take as many young people as possible to university studies through a free education scheme, largely supported by their shares in the Porgera mine. The poorly educated landowners also need financial literacy training to be able to put the profits of the mine into rewarding community and family investments. Otherwise, everything is being instantly squandered as it can be frequently observed with the incomes of those undertaking alluvial mining. A different and better handling of the financial benefits would also minimise the abuse of alcohol and illicit substances, itself a considerable cause of violence in the mining town of Porgera.

Furthermore, with the remaining life span of the mine estimated at just twenty years, the landowners must think what comes next for themselves, and for the Porgera Valley. It is very hard to predict anything for such a remote area, some 650 kms from the closest port of Lae, in an area which is apparently unfit for any alternative sort of development or investment, largely devastated by massive ore extraction and large-scale tailings disposal, with its people presumably on the run as soon as jobs and incomes again dry up.

The forest will most likely reclaim every inch of land and bury everything again into perennial oblivion.

* in charge of advocacy for Caritas Papua New Guinea

17/08/2022 11:23

.png)