Scandal erupts over wartime experiments with leprosy drug

Five other sanatoriums report having administered ‘Koha’ on an experimental basis during World War II. The drug was developed by the army, which imposed its use in several centres despite its side effects and associated deaths. The army imposed its use by ‘instilling terror’.

Tokyo (AsiaNews) - At least five national leprosy sanatoriums during and after World War II reported administering an experimental drug called ‘Koha’ to their patients, which caused serious side effects in some of them. The discovery follows the publication in June 2024 of an investigative report by the Kikuchi-Keifuen leprosarium, located in Koshi, Kumamoto Prefecture, which revealed the practice and led to in-depth investigations in other facilities. This is a sensitive issue for Japan, not least because of the conditions of segregation and abuse suffered by patients and their families.

In June, the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun launched an investigation into the matter, contacting 12 sanatoriums in the country, excluding Kikuchi-Keifuen. Analysis of documents and medical records confirmed that the experimental drug was administered in several centres: the Suruga National Sanatorium in Shizuoka Prefecture; the Oshima-Seishoen Sanatorium in Takamatsu; the Tama-Zenshoen sanatorium in Tokyo; the Nagashima-Aiseien in Okayama Prefecture; and finally the Hoshizuka-Keiaien sanatorium in Kagoshima Prefecture.

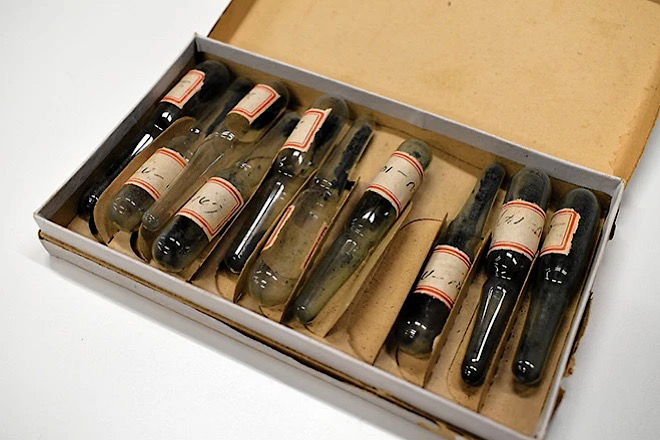

Koha, composed of cryptocin, a photosensitive dye, was developed by the army of the former Japanese Empire, which was interested in its application in the treatment of frostbite and severe cold burns. Officers commissioned research on the experimental drug at Kumamoto University School of Medicine, still a renowned medical university today. After apparent success on patients with tuberculosis, which involves bacteria similar to Mycobacterium leprae, the drug was tested on patients with leprosy.

The director of Kikuchi-Keifuen was commissioned by the Seventh Research Centre of the Army Technical Command to conduct an experimental administration involving 472 residents of the sanatorium between 1942 and 1947. Nine patients died during the trial period, with two deaths suspected of being directly linked to Koha. In addition, a thorough examination of the medical records of all 998 residents of the Suruga sanatorium is underway to determine the use of the drug and its effects. Director Shinichi Kitajima confirmed the administration of the drug, as revealed by a study of post-war medical records.

Staff, bound by professional secrecy, are carefully examining the medical records one by one. The director explains that the task will require ‘time to ascertain all the facts.’ ‘It is possible that other previously unknown elements will come to light. We must establish rules for the storage of medical records and documents,’ Kitajima said. Information on the administration of Koha at Tama-Zenshoen and Oshima-Seishoen was found in the 1947 issue of the Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, now preserved at the National Museum of Hansen's Disease. According to the journal, the director of Tama-Zenshoen reported that out of 175 cases, use was discontinued in 72 within three months, while in 103 it continued for between four and eight months. The facility had to discontinue administration in 57 cases due to deteriorating health.

The director of the Oshima-Seishoen sanatorium also reported administering Koha to 180 people. According to Tsuneji Matsumoto, 93, in 1944 a doctor announced to the young residents of the facility the development of a “new drug for leprosy”. Again, records indicate that Koha was administered to a group of people. According to the elderly man, who entered the centre in July 1942 and still lives there today, the drug was administered under the pretext of treating leprosy. He recalls that the “thin, flat tablet” was taken once a day before noon and that after taking it he felt dizzy and had blurred vision. He also reports that other people around him suffered from fever or purulent wounds. One woman lost her hair. Due to these painful side effects, some patients subsequently refused to take the drug, which was administered for a period of between six months and a year. However, one day, without any explanation, the prescription was abruptly discontinued. He later learned that it was the army that had ordered the suspension. ‘The doctors at the sanatorium,’ he concludes, ‘could not refuse because the military instilled fear.’

.png)